5 Factors Shaping New Jersey Healthcare

Challenges and opportunities continue for hospitals in a post-pandemic world.

On Apr 11, 20242024 marks the first year that our healthcare system has been free from a national public health emergency since the earliest days of 2020. However, that doesn’t mean a return to the pre-pandemic status quo. A confluence of factors – both pre-existing and emerging – are creating new pressures and opportunities for New Jersey’s healthcare community and the patients and communities they serve. Here are some of the leading factors shaping New Jersey healthcare today.

Sicker Patients

The people cared for in New Jersey hospitals are experiencing more severe levels of illness than ever before. The proportion of hospital patients with a “major” or “extreme” level of illness now reaches more than 40%, according to a 2023 analysis by the Center for Health Analytics, Research and Transformation (CHART) at the New Jersey Hospital Association. That’s an increase of 21% between 2019 and 2022. These designations of illness level are measured by diagnosis codes called the All-Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group. These codes, commonly called DRGs, assign hospital inpatients a severity level of 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (major) or 4 (extreme).

The trend is seen across racial and ethnic groups. In 2019, Black and White patients were more likely to be hospitalized with “major” or “extreme” illness compared with other groups. However, by 2022, every group – including Asians, Hispanics, American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian and multiracial – experienced similar levels of increased severity of illness, according to CHART’s data analysis.

This growing concern comes against the backdrop of an aging population. The 65-plus age group was the fastest growing in New Jersey between 2010 and 2022, increasing 35.4% in that 12-year period, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. A 20-year projection by the New Jersey Department of Labor predicts that the 65 and over demographic is projected to grow by 68.7% between 2012 and 2032.

The average New Jerseyan is living to age 80, compared with a national average of 78.5, according to Census data for 2022. That ranks New Jersey 7th highest in the United States for life expectancy.

“As the Baby Boomers age, the profile of today’s hospital patient is sicker and older,” says New Jersey Hospital Association President and CEO Cathy Bennett. “New Jersey is home to nationally recognized hospitals, but our care teams are challenged like never before, caring for patients whose needs are incredibly complex.”

Workforce Shortage

The workforce shortage that has gripped healthcare since before the pandemic shows no signs of abating. The U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration projects that New Jersey will experience a shortage of 11,400 nurses by 2030 – the third highest in the nation. The shortage is fueled by a number of factors. The healthcare workforce is aging, including the nursing ranks. In New Jersey, the highest proportion of nurses are in the 56-65 age group – representing one in every four nurses, according to the New Jersey Collaborating Center for Nursing (NJCCN). And, during the pandemic, no profession was more important – and more impacted – than healthcare professionals. The National Council for State Boards of Nursing estimates that 100,000 US nurses left the workforce during the pandemic, a number that is expected to swell to 900,000 nurses by 2027. For New Jersey’s hospitals, that means:

- The RN vacancy rate has almost tripled in a three-year period, and currently stands at 21.5%.

- The Nurse Extender vacancy rate (certified nurse assistants and other team members) has more than doubled in a three-year period, and currently stands at 26.4%.

The irony is that even in the grips of a deep nursing shortage, nursing schools are turning away qualified students due to insufficient capacity in the education system. New Jersey nursing schools report that a shortage of nurse faculty and scarcity of clinical sites to prepare future nurses as the top reasons that qualified students are denied admission, according to the 2024 Nursing Data & Analysis report from the NJCCN.

The supply-and-demand imbalance persists even as healthcare employers offer very competitive salaries and other economic incentives like sign-on bonuses, retention bonuses and greater pay differentials for overnight and weekend shifts. Other benefits and incentives include scholarships, grants, student loan redemption and tuition reimbursement.

Amid the persistent shortage of nurses, new technology and care models offer promising solutions. Technology, like telehealth and remote patient monitoring, increases access to care and allows individuals to be cared for safely in their homes, while also allowing clinical teams to practice in a more flexible environment and schedule. Within the hospital, team-based care is a model that taps the talents of the entire healthcare team to provide coordinated care to the patient; it’s a more integrated approach that spreads tasks among many qualified professionals.

“Any organization benefits from better use of the diverse talents of its team members,” says Bennett. “That same premise applies to team-based care that engages physicians, nurses, therapists, nutritionists, care technicians, social workers, pharmacists and others. It improves the patient experience, elevates our clinical staffs’ roles and makes caring more efficient.”

Insurance Pressures

Thanks to the Affordable Care Act and expansion of Medicaid, a record-high number of New Jerseyans have health insurance. However, health insurers’ practices increasingly are under scrutiny for the barriers they place before patients and the burdens they impose on the healthcare delivery system. A survey of health consumers last year by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that nearly six out of 10 respondents (58%) in the past 12 months reported problems using their health insurance – such as denied claims and pre-authorization issues. Among those who experienced a problem with their insurance, 17% said they were unable to receive the recommended care because the problem wasn’t resolved, and 28% said they were forced to pay more than expected for their care.

Those same obstacles also impact hospitals and other healthcare providers on a large scale. In 2022, 11% of all claims nationally were denied by insurers, up from 8% in one-year’s time, according to a national analysis. Those denials – primarily prior-authorization denials – cost physicians and hospitals more than $1.6 billion a month.

“Healthcare providers are seeing excessive prior authorization delays and denials, slow payments from insurers, and downcoded or denied payments – in other words: slow, low or no payment,” Bennett says. “These maneuvers have a deep impact on patients and providers alike. They create obstacles for people in need of care and shortchange healthcare facilities at a time when patients’ needs are greater than ever.”

Another insurance trend to watch: Medicare enrollment growth as Baby Boomers reach retirement age. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimates that Medicare enrollment will grow 7.8% annually from 2025 to 2031. Combined, Medicare and Medicaid enrollment is projected to grow twice as fast as private insurance.

Medicare beneficiaries make up 40% of patient volume in New Jersey hospitals. Because Medicare pays hospitals at rates below the actual costs of delivering care, New Jersey hospitals are short-changed about $250 million over a 12-month period. That shifts the burden to commercial payers and self-pay patients to help make up the shortfall. In a Medicare enrollment boom, those pressures will intensify.

“Our hospitals are filling the gaps when government programs like Medicare and Medicaid pay hospitals less-than-cost for the care they provide,” Bennett says.

Mental Health Needs

Numerous studies document the skyrocketing demand for mental health services following the pandemic. The prevalence of depression and anxiety jumped 25% globally in the first year of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization, with little sign of improvement. In the US, behavioral health volumes in 2022 were 18% higher than before COVID, according to Trilliant Health, a market research and analytics firm. Young people under the age of 18 experienced greatly elevated rates of certain behavioral health conditions, including a 107% increase in eating disorder diagnoses and a 44% increase in depressive disorders, according to the Trilliant report.

The need has outpaced the available supply of treatment services, particularly for residential and community-based services. As a result, hospital emergency departments frequently become the destination for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis.

NJHA’s CHART team identified this trend in the first year of the pandemic, especially for young people. Consider these impacts:

- From April through December 2020, the proportion of those under 18 years presenting to an emergency department in New Jersey with a primary or secondary diagnosis for depressive disorders increased by approximately 84% compared to the same period in 2019.

- Anxiety among this age group increased more than 74%.

- For all age groups combined, the proportion of drug/substance use diagnoses increased approximately 29% in the pandemic’s first year. The proportion of drug/substance abuse diagnoses for children and adolescents, while a small percentage overall (just above 1% of all substance use disorder claims), jumped 91%.

This growing demand for services may reflect efforts to de-stigmatize mental health and encourage individuals to care for their mental and emotional well-being, and that’s a good thing, Bennett says. However, it also reveals cracks in the system of care that make it increasingly difficult for individuals to get an appointment with a mental health professional, access a local treatment program, or locate a bed in an inpatient treatment program.

“There is a pressing need for additional resources, coordination and modernization in the mental health system of care,” Bennett says. “Hospital emergency departments (ED) are always open, and they often become the entry point for those in need of mental health services, but they were never intended to be an end point for that care.”

Indeed, the Trilliant Health study found that 84% of patients who went to the ED for alcohol or substance use disorder treatment did not access follow-up inpatient or residential treatment center care within 60 days.

“One of the responsibilities of our broad system of care is to address the barriers or logjams that prevent individuals from getting timely access to the appropriate place for care,” says Bill Arnold, executive vice president and southern region president for RWJBarnabas Health and CEO of Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, who also serves as 2024 NJHA Board Chair. “We need additional mental health capacity so that New Jerseyans can get the right care in the setting that’s designed for their sustained treatment and recovery.”

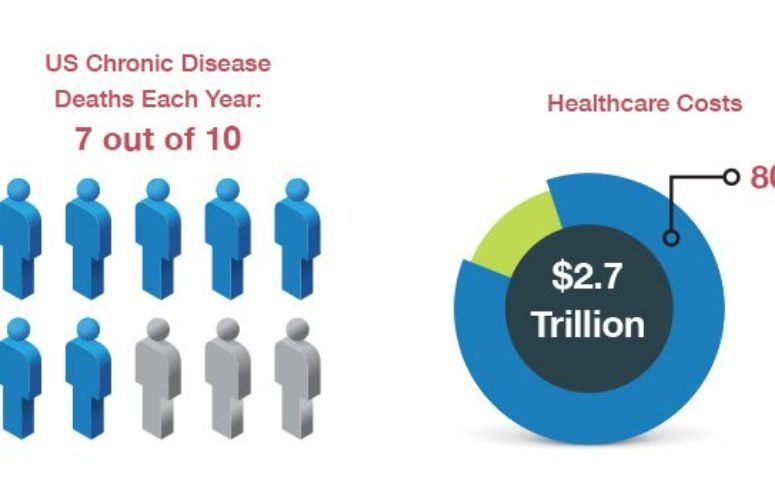

Healthy Communities

Studies suggest that 80% or more of a person’s health status is influenced by social, environmental and socioeconomic factors, beyond health services. As anchors of their communities, hospitals recognize the importance of social determinants of health in improving health, creating equity, and increasing healthcare value. New Jersey hospitals provide nearly $3.5 billion annually in community benefit programming to improve the lives of New Jerseyans. Roughly 12% of every dollar spent by New Jersey hospitals is devoted to these community health initiatives.

The unpaid costs of delivering free and discounted care to the working poor, uninsured and other vulnerable patients total more than $770 million annually among New Jersey hospitals. However, the financial investment spans numerous additional areas of social responsibility that address local needs to create health and opportunity. Examples include:

- The Eat Well Food Farmacy at Virtua Health, which fills “prescriptions” for fresh produce and other healthy foods for individuals experiencing hunger and food insecurity.

- Hackensack Meridian Health providing single-parent students at the JFK-Muhlenberg School of Nursing in Plainfield with scholarships and rent-free living as they pursue their career goals.

- RWJBarnabas Health’s commitment to local hiring and purchasing, which has reached more than $181 million over three years to create jobs and economic opportunities for individuals and small businesses.

- Overlook Medical Center, part of Atlantic Health System, empowering its clinical teams to identify human trafficking victims in the emergency department and help bring them to safety.

- A partnership between Valley Hospital and local school nurses reaching families at risk of losing their insurance coverage and helping them re-enroll during the Medicaid re-eligibility period.

- Englewood Hospital distributing free naloxone kits throughout the community to prevent unnecessary deaths and then connect individuals with support services. Roughly 3,000 New Jerseyans annually lose their lives in drug overdoses.

All told, hospitals’ community benefit programs interact with individuals in a total of 15 million encounters annually, providing a wide range of support and services.

“Hospitals’ roots run deep,” Arnold says. “Hospitals and health systems invest in community wellness, social needs, jobs and economic opportunity, and provide free and discounted care for those who need it. They are the anchor institutions in our communities that are always open and able to provide care to all who need it.”

To access more business news, visit NJB News Now.

Related Articles: