The NJ Biotech Boom

New Jersey is a key location for many biotechnology firms, and, more broadly, recent innovations – driven in part by supercomputers and data analytics – are arguably marking the most innovative era in biotech molecular-level progress.

By George N. Saliba, Managing Editor On Jun 25, 2018Despite often-voiced concerns about the Garden State’s business climate, the fact remains that biopharmaceutical companies are not able to locate just anywhere in the world, since – among other requirements – they need access to a workforce trained in the sciences (low– and mid-level workers usually must be recruited from a local population, as opposed to more senior-level positions that may command workers from around the world).

New Jersey delivers scientific workers in spades. The state also offers access to major airports as well as the capital markets of Manhattan – additional advantages for biotechs whose individually nascent science may demand massive funding on the path toward treating patients.

And while New Jersey was home to just 30 biotechnology firms in 1994, today more than 350 such companies dot the state’s landscape, an outcome that not only reflects New Jersey’s “Medicine Chest of the World” history, but also reveals a rapidly advancing scientific community that has sequenced the human genome and can avail itself of potent supercomputers (such currently-advanced tools did not exist in 1994).

Robert Petit, chief scientific officer at the biotechnology firm Advaxis, says, “I am not certain that there are too many places in the world where this type of biotech boom is possible, outside of New Jersey. New Jersey is No. 1 on the list. Eighty percent of the pharma industry exists in the corridor from Connecticut down to Wilmington, Delaware. A lot of it is along [New Jersey’s Route] 1 corridor, because we have all this expertise, concentrated, here.”

Petit cites: New Jersey’s higher education “products” of technology and young workers; the presence of Big Pharma, which houses experienced people and management; and, again, access to financial markets.

An additional component to the broader life sciences company equation is that “traditional” pharmaceutical firms have long witnessed many patents expire for their blockbuster, revenue-generating medicines, and their science is turned over to the world’s generic drug makers. This may be a boon for patients’ budgets, but without revenue streams, some argue that new research and development efforts within large companies are constrained partly for this reason.

Traditional pharmaceutical companies have, thus, for years striven to: acquire smaller biotechnology firms and gain from the latter firms’ discoveries and agile corporate size; pursue treating “rare diseases” (those globally affecting 200,000 patients or fewer) as a business strategy; and, more broadly, look to global markets with billions of potential patients. So-called “personalized medicine” has also been developed, where – in effect – the drugs are tailored to individuals’ DNA and other unique qualities.

Advaxis’ Petit tells New Jersey Business magazine, “[Big Pharma companies] still have their own research groups and develop their own products internally, but, very often, when the company is large, and they look at a gap in their portfolio, the next thing they do is go out looking for late-stage products. These might be from biotechs – (products) that are on the verge of being approved – that [Big Pharma] can better commercialize.”

The dynamics affecting financing for biotechnology companies have also evolved, as Chip Baird, chief financial officer of Amicus Therapeutics, explains: “What is interesting and different is that in recent years, there is more and more availability of risk capital of financing for biotech companies and earlier-stage biotech companies,” he says. “In the past, those companies would have to turn to pharma to continue their growth. Certainly for a company like Amicus, we have been successful in raising a great deal of capital to build our business: We own the global rights to all of our programs; we are commercially launched; and we are [experiencing] tremendous growth in terms of headcount and in terms of revenue – and an extension of the pipeline.”

He adds, “With additional capital available, you are today seeing more and more [biotech] companies really get to that stage of commercial launch and growth. And I think that is healthy for the broader ecosystem.”

Advaxis’ Petit cites the benefit of a free-wheeling innovation a biotechnology company may afford its scientists (sans a large corporate structure), but he adds that traditional pharma does have access to substantial data management and quality assurance processes, for example.

Petit says, “Big Pharma needs these new products, and the biotechs have the innovation and the creativity. A lot of us are executives from Big Pharma too, so we know sort of how to generate the data that is necessary for Big Pharma to look at it and say, ‘OK. This is going to check all of our boxes; this is something we can bring into our organization and make available to a lot of people.’”

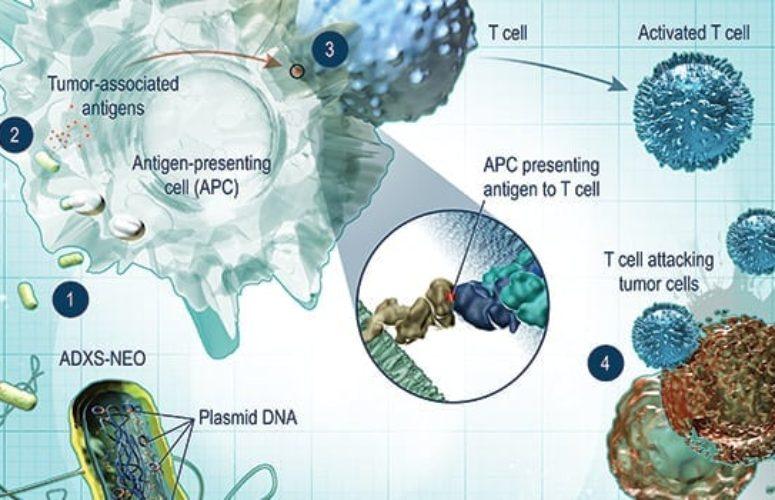

Petit’s above comments are separate and apart from Advaxis’ current projects, which offer a glimpse into today’s leading-edge science and might have once resided solely within the pages of a 1950s-era science fiction novel. During a 40-minute interview with New Jersey Business, Petit detailed specific iterations of what might be translated into layperson’s terms as: Various approaches to attaching bacteria to only a person’s cancer tumor, and then having that person’s natural immune system destroy said bacteria – and the cancerous tumor – in the process.

While that may be an oversimplification, Petit summarizes, “What we have been able to do with our Advaxis platform is take different worlds – the world of infectious disease; the world of cancer and cancer treatment, and cancer immunotherapy; and the world of artificial intelligence, computer technology [and] bioinformatics – and put all this information together into a composite treatment for cancer. It seeks to use the ability of the bacteria to get the immune system’s attention, and then direct the immune system’s attention against the very mutations that make that cancer malignant.”

Based in Princeton with approximately 100 employees, Advaxis’ clinical trials for several iterations of the above scenario are set to start soon, since the products have already been designed and developed, and many of them have been sent through manufacturing training.

Meanwhile, the aforementioned Amicus Therapeutics, with approximately 400 employees, may be treating some 5,000 patients in five years (by the end of the year 2023), and is already among one of the more heralded biotechnology company success stories.

More About New Jersey

As some New Jersey pharmaceutical companies face difficulties, their employees may drift toward various biotechnology companies, where they can lend their expertise. Amicus’ Baird explains, “There is a lot of big pharma challenge in the state, and being able to effectively recruit the clinicians, the bio-statisticians and the regulatory experts who have built careers at pharma companies and are now looking to do something in a second act [is beneficial]. They are looking at companies like Amicus, where they can make a direct and comparable impact on patients. This has been a win-win for Amicus and for people in the state.”

Pharma

Vanessa Broadhurst, president, of cardiovascular and metabolism, at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, says, “Johnson & Johnson [of which Janssen is a subsidiary] has been a proud member of the New Jersey business community for more than 130 years. Today, our pharmaceuticals business is a growth engine for the company, delivering 7.5 percent operational growth in Q1 2018.”

She adds, “At Janssen, we believe that a great idea can come from anywhere – inside or outside our company – and we are committed to helping those ideas become healthcare solutions for patients. Historically, we have seen around 50 percent of our new medicines come from external partnerships. In recent years, we have really focused on developing new ways to find and partner with biotech companies, creating an ecosystem with our Innovation Centers, JLABS and business development teams. … Earlier this year, we announced that through our Innovation Centers we executed more than 350 collaborations since their establishment in 2012.”

For the Garden State overall, the website for the trade association HealthCare Institute of New Jersey (HINJ) reveals that “New Jersey is home to more biopharmaceutical companies than any other state in the country, or any other country in the world.” Moreover, HINJ also reveals that, “13 of the world’s top 20 research-based biopharmaceutical companies maintain a presence in New Jersey; 12 of the world’s top 20 medical technology companies maintain a presence in New Jersey; $104.7 billion total economic output is supported by the biopharmaceutical sector in New Jersey in 2014; 78,447 New Jersey jobs are directly supported by the biopharmaceutical and medical device sectors; and 425,867 New Jersey jobs are supported, directly or indirectly, by the biopharmaceutical and medical device sectors,” for example.

Echoing the sentiments of others, HINJ also reveals that New Jersey is “The No. 1 state for biotech growth potential.”

Other Considerations

While there is much focus on biotechnology companies in New Jersey, there are other, tangentially-related entities, including, but certainly not limited to companies like Sweedesboro-based Wedgewood Pharmacy, a compounding pharmacy that largely serves the veterinarian market. Compounding pharmacies respond to requests from doctors and veterinarians when those professionals cannot access medications in doses or preparations that they need; the medication is specially formulated by the compounding pharmacy.

Wedgewood Pharmacy’s President and CEO Marcy A. Bliss tells New Jersey Business, “I think in the animal health [sphere], it is the fact that people now consider pets part of their families. We call that the humanization of pets. Fifteen years ago, if peoples’ pets had certain conditions that were life-long and chronic, they used to put their pets down. But people don’t accept that anymore, especially millennials and the Baby Boomers. They would rather take care of their pets sometimes than take care of their own needs and their own health.”

Conclusion

On the one hand, the nation is grappling with issues ranging from those that are geopolitical in nature and an opioid epidemic scourge, to widespread obesity in the general population and horrific events like mass shootings. On the other hand, when one turns away from the news media long enough to breath, he or she may realize that we live in an era of science and medical technology never seen since the first hominoids roamed the earth. Moreover, from Route 1 to Franklin Lakes, our state is a significant component of this unfolding saga that affects much of the world’s population.

To access more business news, visit NJB News Now.

Related Articles: